A Passion for Learning

We take so much for granted in our lives. Shelter, healthcare, free speech… the list goes on. And yet, there are still people who cannot see how fortunate they truly are. Education is something that many people take for granted, especially those who have never known otherwise.

The documentary “Everybody’s Children” shares the story of two refugees who fled to Canada and are attempting to integrate into our society. While there proves to be a lack of support in place for refugees, the two individuals, Joyce and Sallieu, never lose faith. Imagine the struggles they are going through: their lives previously were not positive, they move to a foreign place, and there is a lack of guidance when they arrive. And yet, they are thankful for everything in their lives.

Two things struck me about this documentary. Joyce demonstrates a strong sense of faith, thanking God for everything he has provided her in her new country. Her ability to hold on to her faith despite everything that happened in her life is a strong testament that God is good to those who have an unwavering faith in Him. The second thing that struck me was Sallieu’s passion for his education. He never once took his education for granted. He consistently tried to be the best student that he could be, striving for the top mark in every class. This got me reflecting…

There is a true lack of passion for learning in many of our schools. Students believe that they are sent there against their will and that it is just a waste of time. Think of all the better things they could be doing: playing video games, sleeping in, watching TV… and yet, they have to come to school for 8 hours a day.

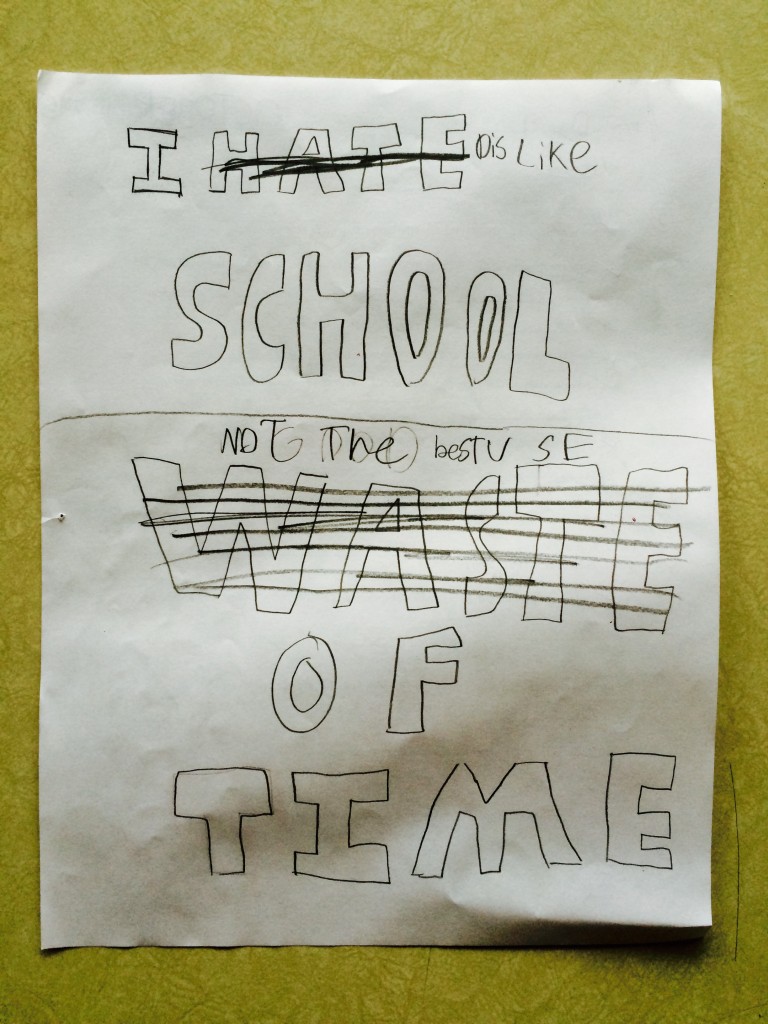

This lack of passion is a problem. No wonder teachers have to implement so much classroom management: we are forcing children to be students that don’t want to be. Take, for example, the back of one of the tests I created for my grade 7 class:

Does this child currently have a passion for learning? No. Is he capable of developing a passion for learning? Most definitely.

Teacher’s have to work that much harder to cater to their students, proving to them that education can be enjoyable. We must work to make education the best part of our students’ day. But more than anything, we must instill in our students a sense of gratitude for the opportunity to learn so that they never forget how fortunate they truly are.

Stop, COLLABORATE, and Listen

I know of way too many teachers to come to school in the morning, close their door, attend to their students, and leave at the end of the day. This isolation is a harsh reality for many teachers in the profession. While some may view this trend as demonstrating full attention to students, this may not be the most beneficial thing for their learning. It is very important that teachers learn to adopt an “open door policy” when it comes to collaborating with their teaching peers.

As someone who loves collaborating with others, it seems like a daunting task to block out other teacher’s ideas and focus on what I am doing. Not to mention, it may not be the most beneficial thing for my students. As Cooper suggests:

“With so little planning time available and so much vital work to be accomplished, we must harness the power of web technology to ‘work smarter, not harder’” (page 233).

Just as the web is a great resource to improve our teaching practice, other teachers in our school are a direct resource that we can use to our, and our student’s, advantage. I think it’s imperative that teachers have a consistent time and place where they can get together with their colleagues to talk and collaborate on ideas. This is a time to talk about what’s working and what isn’t working, gather ideas on what to do with the student that just won’t do anything, vent frustrations, and perhaps even split the workload!

Especially as someone who is currently a teacher candidate, collaboration is key. I like to hear innovated ideas that other teachers have implemented to improve learning for their students. Unfortunately, much of the time teachers have to collaborate is during their lunch periods. If teachers don’t reach out to one another to collaborate, there may never be the opportunity to learn from one another, which brings us back to the “show up, teacher, go home” trend.

Especially as someone who is currently a teacher candidate, collaboration is key. I like to hear innovated ideas that other teachers have implemented to improve learning for their students. Unfortunately, much of the time teachers have to collaborate is during their lunch periods. If teachers don’t reach out to one another to collaborate, there may never be the opportunity to learn from one another, which brings us back to the “show up, teacher, go home” trend.

Ideally, there would be some kind of system that can be put in place to make collaboration feasible and encouraged among teachers. This can be with teachers of the same subject, same grade level, or teachers who have worked with the same students before. Additionally, Cooper speaks of the importance to collaborate with all kinds of teachers:

“While it’s natural to collaborate with a colleague who teaches the same course, it can be just as valuable to work with a teacher in a different department” (page 238).

When teachers collaborate, teaching practices improve, teacher performance increases, and student receive a well-rounded education. Seems like the right approach to me…

A Teacher’s Prayer #1

Ask, Don’t Tell: The Classroom Environment

The classroom is a very unique concept. Students and a teacher are in a room together for 7 hours every day, which can be longer than some students spend awake in their own homes each day. What does this mean for the teacher, and more importantly, what does this mean for the students?

Hopkins (2011) and Ayers (2010) introduce us to the world of positive environment creation, in relation to our school classrooms. Hopkins presents five key themes that every classroom should account for:

- Everyone has their own unique and equally valued perspective

- Thoughts influence emotions, emotions influence actions

- Empathy and consideration

- Needs and unmet needs

- Collective responsibility for problem solving and decision making

Not only do these themes encourage the development of an accepting and student-centred classroom, but they also promote the well-being of the students. This can be either social, emotional, cognitive, psychological, or otherwise. All of these themes are key to creating the highest functioning future generation.

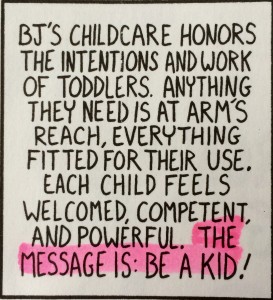

Ayers complements these themes by discussing the multiple purposes that classrooms face and the challenges of incorporating all of these needs into one classroom environment. The following quote struck me from this reading:

We as teachers have our own ideas when it comes to creating a learning environment, but sometimes our “adultness” removes our focus away from our students. We must consciously remind ourselves that the classroom is a shared environment and that we must hear from our students in regards to what environment they learn best in; we must ask, not tell our students where they want to learn.

In was regular during my time in elementary school that I would walk into a classroom on the first day of school and leave on the last day without the classroom environment changing. This meant that the same store-bought posters defining “perseverance” and telling us to “stand out and be unique” stared back at us for 10 months straight. Did that poster encourage me to persevere throughout the year? Not really. Would the concept have had a larger impression on me had we all created a piece of art that defined what perseverance meant to us, and then had them posted around the classroom? Probably. Why? Because the classroom would have been my environment for learning, a product of my creativity and learning.

This is exactly why the teacher must learn to step back from their authoritative role when it comes to creating a positive and enriching learning environment. The classroom might be home for the next 10 months to 31 people: 30 of which are students and 1 being the teacher. Who, then, is the environment truly for? Let students create their collective learning environment. Allow them to collaborate on the rules and goals of the classroom. Most importantly, ensure the students feel at home and included. The more comfortable the students are in their environment, the more enriching their learning will be.

Report Card Wows and Woes

Some kids get a laptop.

Some kids get grounded.

Other kids get a pat on the back. (… me)

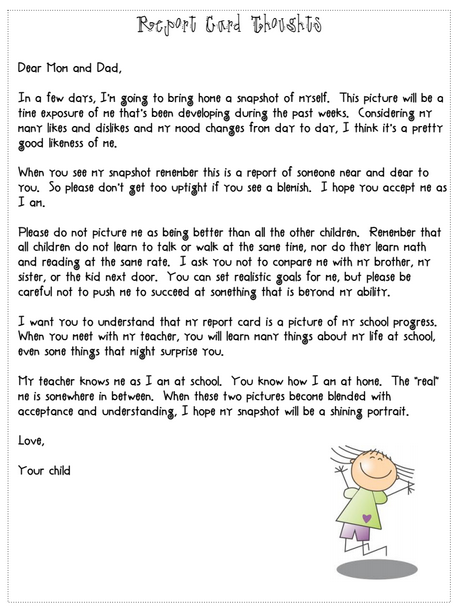

In a child’s educational career, report card season can be one of the scariest and most dreaded times of the year. Every student wants to do well in school, but when it comes to report cards, their successes or shortcomings are in plain view for their teachers and parents to see. Can, then, the stress that comes along with distributing report cards be overshadowed because of the importance they contain?

Many teachers would probably say that report cards might be the least favourite part of their job. No, not because they take a very long time to write. Rather, it is difficult for teachers to represent months of a student’s accomplishments and experiences on a single sheet of paper represented by a single grade. If not analyzed properly, students and teachers might only see the grade and pass judgement based on that. However, it is almost impossible to paint a complete picture a months of work for anyone under those circumstances.

Despite multiple criticisms about the process, report cards are essential for informing parents of student progress, as they traditionally serve as the overall measure of assessment of a child’s success in school. Growing Success, albeit a government document, discusses the purpose of report cards:

“The report card grade represents a student’s achievement of overall curriculum expectations, as demonstrated to that point in time” (page 39).

This information can be used to communicate to students, parents, school administration, psychologists, and even college and university admission departments. So, yes, report cards do serve a useful purpose in the educational development of a student.

But back to my initial question: Can the stress that comes along with distributing report cards be overshadowed because of the importance they contain? I think the main problem with this whole situation is that there is stress, period. I understand that some students may not be proud of a particular mark they received, nor do they want to share it with their parents. Cooper had a great response to this topic, as one of his Guiding Principles states:

“A report card grade should not be a surprise to the teacher who determine it, nor to the student and parent who receive it” (page 212).

This is to say that teachers should be aware of all of their student’s progress, the student should be a self-reflective learner and know where they sit in terms of their achievement, and parents should be active members of their child’s education, thus getting involved with their learning and having check-ins with the teacher along the way.

And if parents or students are still scared about the upcoming report card distribution, you could always send home this letter a few days before they’re released:

Rubrics: A Teacher’s Best Friend or Worst Nightmare?

Something that seems as straightforward as outlining four varying levels of accomplishment is far more complex than most people may expect. With the pressure of having to justify a given mark to students, teachers, or administrators, teachers have to be sure that the rubric provides adequate and accurate information about what is expected of the students’ work. All that work just to let a student know what mark they achieved? It’s far more than that. As Andrade states in her article Teaching With Rubrics: The Good, The Bad, And The Ugly:

“We use them to clarify our learning goals, design instruction that addresses those goals, communicate the goals to students, guide our feedback on students’ progress toward the goals, and judge final products in terms of the degree to which the goals were met” (page 27).

We all know how busy teacher’s are, which is why I found comfort in the fact that rubrics are not just simply statements of student achievement; rather, they are a product of the planning, implementation, and assessment processes. But what happens when we have students learning at different levels in our classroom (i.e. IEPs)?

When it comes to instructing students at varying levels, Cooper encourages everyone to adopt “differentiation”:

“[…] beginning with the same unit plan, lesson, or assessment task and then differentiating each of these according to the needs of groups of students in a given class” (page 136).

In Cooper’s text, we also learned that it’s not necessary to create rubrics for each individual student. As long as the content standards are in line with what is expected of each student, then the rubric can remain the same; the requirements of whatever is being graded will be the only thing that actually differs.

In conclusion, rubrics are a great tool, not only for the teacher but for students as well. Rubrics outline what is expected of them and what is required to achieve each specific grade level. Perhaps more importantly, rubrics answer the common question, “Why am I learning this?” by display to students the various learning outcomes that are clearly outlined.

Student Voice: A Response to “The Class”

The Class/Entre les murs introduces us to a year of teaching in an intercity school in Paris. With a group of unmotivated and disrespectful students, teachers are not able to take a regular approach to teaching; they must create their own style that targets the students within their classroom. Throughout the film, the audience questions the topic of “student voice” and whether or not M. Marin and the school are providing their students with enough opportunities to achieve this. Student voice involves providing students with a platform to share their input and be heard in a receptive way. While the concept seems great, just how valuable is student voice?

I often catch myself asking the question, “What is the ultimate purpose of education?” Is it simply to learn a bunch of different things that the government deems valuable? Is it to prepare students to find a job and work? Is it to teach students to be contributing members of society? What I’ve come to find is that the purpose of education is far more complex, proving to have more purposes that I could ever define. But how much more could the students gain if they were contributing to their own education?

Students learn about issues in the world (pollution, racism, etc.) and people who are remembered for something great (Laura Secord), but are students being prepared to tackle these issues and be remembered for their contributions? I believe that teaching students about being a leader and a contributing member of society isn’t enough; we must provide them with the tools and characteristics to become that leader. By allowing students to have their voice heard and to be an active contributor to their education, they will come to realize that their actions and decisions can make a difference and they can bring positive change to the world around them.

Edutopia provides us with three reasons why student voice is key:

- What students have to say matters in how learning happens.

- Students have untapped expertise and knowledge that can bring renewed relevance and authenticity to classrooms and school reform efforts.

- Students benefit from opportunities to practice the problem solving, leadership and creative thinking required to participate in a decision-making school community.

http://www.edutopia.org/blog/sammamish-2-including-student-voice-bill-palmer

As a teacher, we must learn to share the power of the classroom with our students, allowing them the opportunity to hold the reigns of their own education. Not only does this make students more engaged in their learning and learn more content because of their engagement, but it prepares them to be the best person that they can be. This is all we can really hope for as teachers.