Indian Residential Schools’ Impact on Canadian Education

I’ll admit, History was not one of my favourite subjects growing up. The way it was taught felt like stories rather than realities. The focus was on devastating harms committed over 50 years ago in countries that seemed to be on the other side of the world. The approach was “this is what happened and this is why we should never do it again”. But what about the devastating harms that occurred right in our own backyards? Why aren’t those topics at the forefront of our history classes? As Canadian’s, should there be a larger focus on being taught information that has a personal connection to each and every one of us, which may even lead us to work towards uniting everyone in our country?

The video We Were Children shares the harsh realities of residential schools in Canada:

“Beginning in the late 1850’s, over 150,000 Aboriginal children were legally forced to attend Indian residential schools in Canada. The schools were part of a wider program of assimilation designed to integrate the Aboriginal population into “Canadian society.” At their peak in the 1950’s, there were 80 Indian Residential schools across the country. Today there are over 80,000 Indian Residential school survivors. The last Indian Residential school closed in 1996” (We Were Children, 2012).

There was so much pain suffered by First Nations, Inuit, and Metis (FNIM) peoples in our country, and yet teachers and the government gloss over or skip altogether the realities of our country’s past. This paints a picture of continual denial, neglecting to incorporate these lessons into our so-called perfect Eurocentric education approach. As Battiste outlines in her book Decolonizing Education:

There was so much pain suffered by First Nations, Inuit, and Metis (FNIM) peoples in our country, and yet teachers and the government gloss over or skip altogether the realities of our country’s past. This paints a picture of continual denial, neglecting to incorporate these lessons into our so-called perfect Eurocentric education approach. As Battiste outlines in her book Decolonizing Education:

“Eurocentric education policies and attempts at assimilation have contributed to major global losses in Indigenous languages and knowledge, and to persistent poverty among Indigenous peoples” (page 25).

The difficult part for the teacher is deciding how to address the issue and the pain of what happened, without turning it into just another history lesson routed in this Eurocentric framework. How do we address this important part of our country’s heritage without placing all FNIM students on a pedestal? What is the best way to present this topic so that students can become aware, learn from the mistakes of the people before us, and use this knowledge to make the world a safer, more inclusive place?

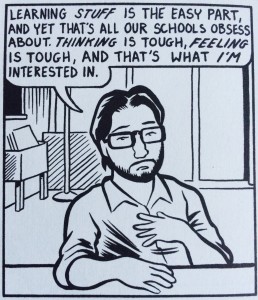

I believe that as more and more people accept the reality of what happened to FNIM people and as education policy adopts a restorative approach to fully including these students in our education, we can begin to heal as a population. The importance of this topic is not to simply teach students, but to make them think and feel. Ayers states:

As Prime Minister Harper admitted in the public apology to First Nations individuals, the residential school system, unfortunately, was very effective in its goal of destroying the Indian in the child. It’s time to celebrate First Nations history, culture, language, ceremony, and worldviews. By incorporating this knowledge consistently throughout the Canadian curriculum, we will not only ensure increased academic success for indigenous students’, but we will also education all students to love their neighbour and cherish our differences.